Freedom to Move, Freedom to Be: The Feldenkrais Method

By Lavinia Plonka

If you know what you are doing, you can do what you want.

— Moshe Feldenkrais

I was in my late 30s, at the height of my performing career, but my body felt like I was ready for the junk heap. My back hurt almost all the time. I was going to the chiropractor, massage therapist, and acupuncturist just to be able to keep getting on the stage. I was convinced that I had something terribly wrong with me. Once, I peeked at the chiropractor’s chart to see my diagnosis. It said “Lumbago.” Wow. Then I looked it up. Lumbago simply means lower back pain. That’s it? Nothing was really wrong with me? Then why the pain?

I was in my late 30s, at the height of my performing career, but my body felt like I was ready for the junk heap. My back hurt almost all the time. I was going to the chiropractor, massage therapist, and acupuncturist just to be able to keep getting on the stage. I was convinced that I had something terribly wrong with me. Once, I peeked at the chiropractor’s chart to see my diagnosis. It said “Lumbago.” Wow. Then I looked it up. Lumbago simply means lower back pain. That’s it? Nothing was really wrong with me? Then why the pain?

One day, while sitting in yet another doctor’s office, I came across an excerpt from a book called The Elusive Obvious by Moshe Feldenkrais. I’d never heard of him, but as I read, light bulbs exploded in my head. Feldenkrais explained that most of our actions are governed by habits we’ve developed over the course of our lives. From the moment we learn to move as babies, we are creating habits that help us turn, reach, walk, drive, make coffee, fall in love, everything. In his book The Power of Habit, author Charles Duhigg says that when we are learning something new, all different parts of the brain light up. Once it’s become a habit, the brain doesn’t work anymore. Instead, the basal ganglia, like some incredibly efficient secretary, delegates the way we accomplish our tasks to the nervous system to leave the brain to think up other things, like solving the world’s energy crisis. What if my back pain was a habit?

One day, while sitting in yet another doctor’s office, I came across an excerpt from a book called The Elusive Obvious by Moshe Feldenkrais. I’d never heard of him, but as I read, light bulbs exploded in my head. Feldenkrais explained that most of our actions are governed by habits we’ve developed over the course of our lives. From the moment we learn to move as babies, we are creating habits that help us turn, reach, walk, drive, make coffee, fall in love, everything. In his book The Power of Habit, author Charles Duhigg says that when we are learning something new, all different parts of the brain light up. Once it’s become a habit, the brain doesn’t work anymore. Instead, the basal ganglia, like some incredibly efficient secretary, delegates the way we accomplish our tasks to the nervous system to leave the brain to think up other things, like solving the world’s energy crisis. What if my back pain was a habit?

|

|

|

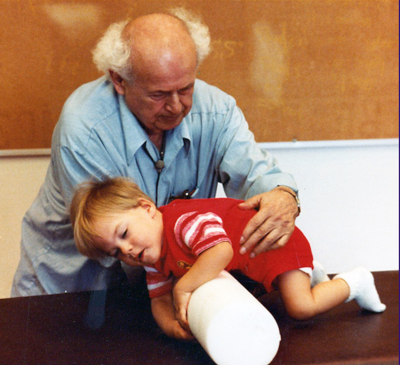

Moshe Feldenkrais

|

Feldenkrais said we develop anxiety patterns that result in tension and holding. This affects our posture. Could that be the reason I was in pain? I went to a Feldenkrais class in New York. It seemed like we were doing virtually nothing. I raised and lowered my head. I breathed. I laid down. It was very relaxing, but really? After the class was over, I was chatting with someone as I bent to tie my shoes. I froze. Stood up. Bent back down. Stood up. “My, my, my back doesn’t hurt!” I blurted.

It’s not flexible bodies, but flexible brains I’m after.

— Moshe Feldenkrais

So how does it work? People ask me all the time, “If there’s no stretching, and no strain, how can we possibly improve?” I love that question. We have been totally indoctrinated into a culture that says, “No pain, no gain.” This “harder is better” principle operates on the assumption that the body is just a stupid machine that must be subjugated by the “mind.” Feldenkrais was one of the first contemporary scientists to propose that the body itself is intelligent. The French neuroscientist Alain Berthol says in his book The Brain’s Sense of Movement, that we have forgotten our sixth sense: the kinesthetic sense, or what is called proprioception. Without a kinesthetic sense, I wouldn’t know I’m touching the keyboard, exactly how far to reach to my teacup, or even where I am in the room. Our kinesthetic sense surrounds us so totally, it’s invisible like asking a fish about water.

Feldenkrais said, “I believe that the unity of mind and body is an objective reality. They are not just parts somehow related to each other, but an inseparable whole while functioning. A brain without a body could not think.” Feldenkrais lessons are called Awareness Through Movement®, not awareness of movement. How you move is how you move through life. Your body/mind is completely governed by your nervous system’s response: to stress, pleasure, shock, and your environment. The gentle movements of the Feldenkrais Method allow you to learn to develop new habits that can reduce pain, improve flexibility, and as Feldenkrais put it, “… restore human dignity.”

The Feldenkrais Method is not a magical mystery. It’s actually based on a very precise study of how we learn. When babies are learning how to lift their heads or roll over, they don’t have a manual, a coach, or even an idea about how to do it. The process becomes one of trial and error, experimentation and discovery. Every baby is unique. While one baby will roll over onto the stomach and be amazed and delighted, another will be so shocked they start crying. This too is part of the learning process. When we learn, we are at the threshold of the unknown. After all, if you already know, then there’s nothing to learn.

Because our first learning experience, and all the attendant ways we approach life and think about things come from this original organic learning experience of movement, Feldenkrais lessons use movement to help us learn about ourselves. Many of the movements come from infant development patterns. Others are subtle investigations into function: how does the shoulder move, how does it relate to the muscles of the back, how does it interfere with easy breathing? Every one of the thousands of lessons comes complete with many questions for the nervous system to investigate. The process of paying attention to the movement is actually more important than the movement itself.

A Feldenkrais teacher does not demonstrate. Instead, the instructions are precise verbal directions that allow each person to explore according to their interest and ability. There is no “best” person in the class. There is no “wrong.” If someone has misinterpreted the movement instruction, the instructor realizes that that person has a different learning process. The suggestion is then re-phrased, developed, and clarified. This helps people break the habit of thinking they have to be told “what is right.” Each person discovers how the movement is right for them.

Feldenkrais lessons can be done by anyone, because anyone can learn. If a person has limitations (“We move according to our perceived self-image,” said Feldenkrais), they can work with the instructor to find greater ease, or simply imagine the movement. It’s now standard practice among athletes, musicians, and others to “visualize” executing a movement. Research has shown that athletic performance actually improves more through use of imagery than through physical drills. Feldenkrais introduced the process of imagining movement over 50 years ago, stating that the nervous system interprets intention as action. This is why the work is so effective for people who have neurological damage, either through birth trauma, stroke, or other illness. By exploring what is possible in a safe learning environment, anyone, from a world-class performer to an elder struggling with balance, can improve their movement and their life.

Movement is life. Without movement, life is unthinkable.

— Moshe Feldenkrais

A mini-Feldenkrais lesson

You can do this lesson right where you're sitting. Sitting on the front of your chair, with your feet flat on the floor, sense your sit bones at the bottom of your pelvis. Slowly begin to roll your pelvis as if you were slumping. Your tailbone moves forward and your lower back moves backward. You may feel your heels wanting to lift, that’s OK. Return to neutral and repeat several times. As you tilt, notice your breath. Can you exhale as you round your back, and inhale as you return? What do you feel in your head and neck? Try gently lowering your head as you tilt your pelvis.

Take a short rest by sitting back in your chair.

Return to the front of your chair and try the opposite movement. Tilt your pelvis so that your lower back arches slightly and your tailbone moves back. Does your chest move? As you tilt your pelvis, let your head look up toward the ceiling. Imagine your whole spine participating in this movement.

After a short rest, return to the front of the chair, and begin alternating the movement of the pelvis — rolling it forward and back. As you arch your back, your head looks up; as you round your back, your head looks down. Make the movement smaller and smaller, till someone walking by wouldn’t even see that you are moving.

As you return to your work, notice that your posture and even your vision may have changed.

Body language expert Lavinia Plonka has helped people improve their movement, behavior, relationships, and careers for over 35 years. Her unique expertise connects the dots between posture, movement, emotions, and the mind. Lavinia’s training and professional career have included theater, dance, yoga, and the martial arts. She has taught the Feldenkrais Method® for over 25 years, and is also a trainer of other practitioners. Lavinia is also a level CL4 teacher of the Alba Method and an Emotional Body instructor.

Body language expert Lavinia Plonka has helped people improve their movement, behavior, relationships, and careers for over 35 years. Her unique expertise connects the dots between posture, movement, emotions, and the mind. Lavinia’s training and professional career have included theater, dance, yoga, and the martial arts. She has taught the Feldenkrais Method® for over 25 years, and is also a trainer of other practitioners. Lavinia is also a level CL4 teacher of the Alba Method and an Emotional Body instructor.

Her professional artistic endeavors include an artist-in-residence for the Guggenheim Museum, and being a movement consultant for theater and television companies around the world — from the Irish National Folk Theater to Nickelodeon. From Esalen to the Council on Aging, from Beijing to Mexico, Lavinia’s popular workshops explore the intersection between movement, emotions, and the mind. She is the director of Asheville Movement Center in Asheville, North Carolina, offering a complete movement curriculum, including workshops and private lessons. Lavinia’s writing includes several books and audio programs, as well as her popular column, CosmiComedy.

Click here to visit Lavinia's website.

Click here to listen to Lavinia read a 7-minute excerpt from her book, What Are You Afraid Of?

Catalyst is produced by The Shift Network to feature inspiring stories and provide information to help shift consciousness and take practical action. To receive Catalyst twice a month, sign up here.

This article appears in: 2020 Catalyst, Issue 9: Somatic Movement Summit